How Do Regular Computers Work?

Regular computers work by acting on tiny switches called bits. Simply by changing the 1’s and 0’s of these switches, computers can do anything, including loading and displaying this website, looking at where your mouse is, running Windows, literally anything.

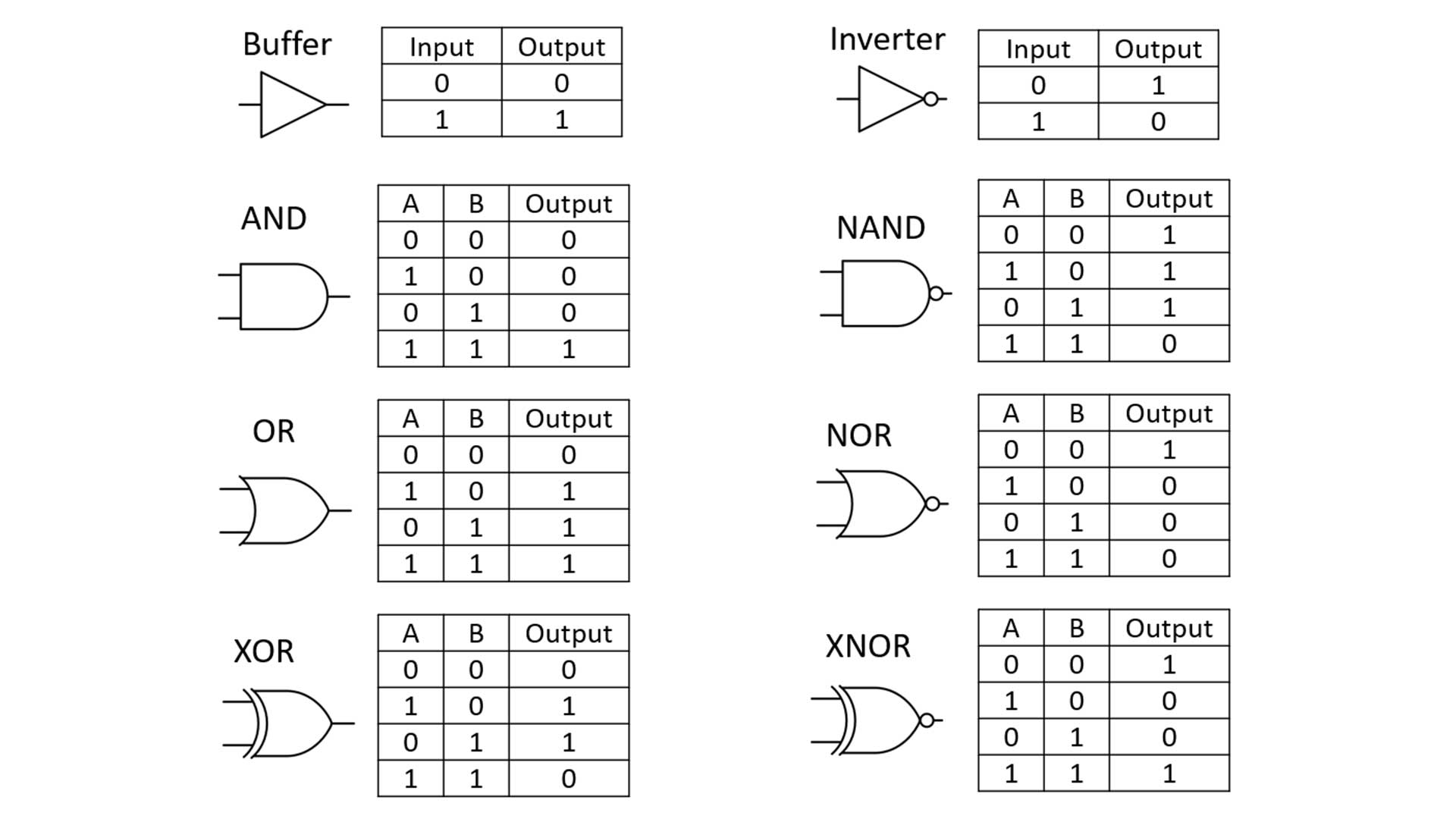

What computers do to these bits is defined by different logic gates. Logic gates take (usually) 2 bits, and output a single 1 or 0 based on a certain operation. Here are the main logic gates and what they do based on the bits inputted:

Different Types of Logic Gates:

Image Courtesy of Global Science Network

Try building your own logic gates, and see what happens with various inputs:

Here’s a challenge: Every single gate can be simulated using only NAND, or only NOR. Try to take two inputs and output the same results as each of the different gates using only NAND gates or only NOR gates.

These switches are all extremely small, about the length of 20 atoms. They have been getting smaller and smaller over time, but soon they won’t be able to physically get smaller. When they reach five atoms across, electrons can leak out and short-circuit the chip or generate so much heat the chips melt. Moore’s Law, stating that the size of transistors (bits) will halve in size every 2 years, will soon be impossible.

Image Courtesy of Wikipedia

How Do Quantum Computers Work?

Quantum computers work on perhaps the smallest unit possible, the atom. Each atom is called a qubit, short for "Quantum bit". Although yes, these are the smallest a bit can be, that is not the main appeal of quantum computers. They are so much faster than regular computers not because of their size, but because of the properties of atoms.

Spin

What exactly is a quantum computer looking at when measuring a qubit? There’s no “switch”, so what it’s measuring is the "spin" of the atom. But what does that mean? An experiment called the "Stern-Gorlach experiment" showed that atoms are always facing either exactly up, 1, or exactly down, 0. When typical magnets are shot between two opposing magnets, the opposing magnets create a force that deflects the smaller magnet up or down depending on its rotation. It can land anywhere between straight up and straight down. However, when electrically neutral atoms are shot through these two magnets, they either face exactly up or exactly down. This means atoms behave like magnets but with only two possible directions: north-south and south-north exactly. This direction of the atom is what the quantum computer is measuring. For a visual explanation, see the video below:

Video Courtesy of toutestquantique.fr

Superposition

The way qubits are expressed is usually as two numbers, the probability of being 1 and the probability of being 0. This is because atoms can be in multiple places at the same time, therefore qubits can be both 1 and 0 at the same time. The problem is, when measured, the atom collapses into one random state. So when we don't look at the atom, it has a different probability of being 1 or 0, but when we look at it or measure it, it becomes either 1 or 0 only based on those probabilities. Qubits are written as the probability of the atom collapsing into 1 or 0 when measured.

Video Courtesy of toutestquantique.fr

Image courtesy of Poetry in Physics

This seems useless at first, but quantum computers have special algorithms that act on the entire superposition at the same time. It acts on every possibility simultaneously and does special computations to get all the outcomes it doesn’t want to destroy each other, leaving only the correct answer to be measured.

On a classical computer, 32 bits can only represent ONE of the numbers from 0 to 4294967295, while 32 qubits can represent ALL numbers from 0 to 4294967295 simultaneously. If we have a special algorithm that cleverly makes all results except for the correct one destroy each other or lower their probabilities, you can go very very fast. It needs to run an algorithm only once for only one superposition of all the numbers, compared to up to 4294967295 repetitions of an algorithm, one for each number.

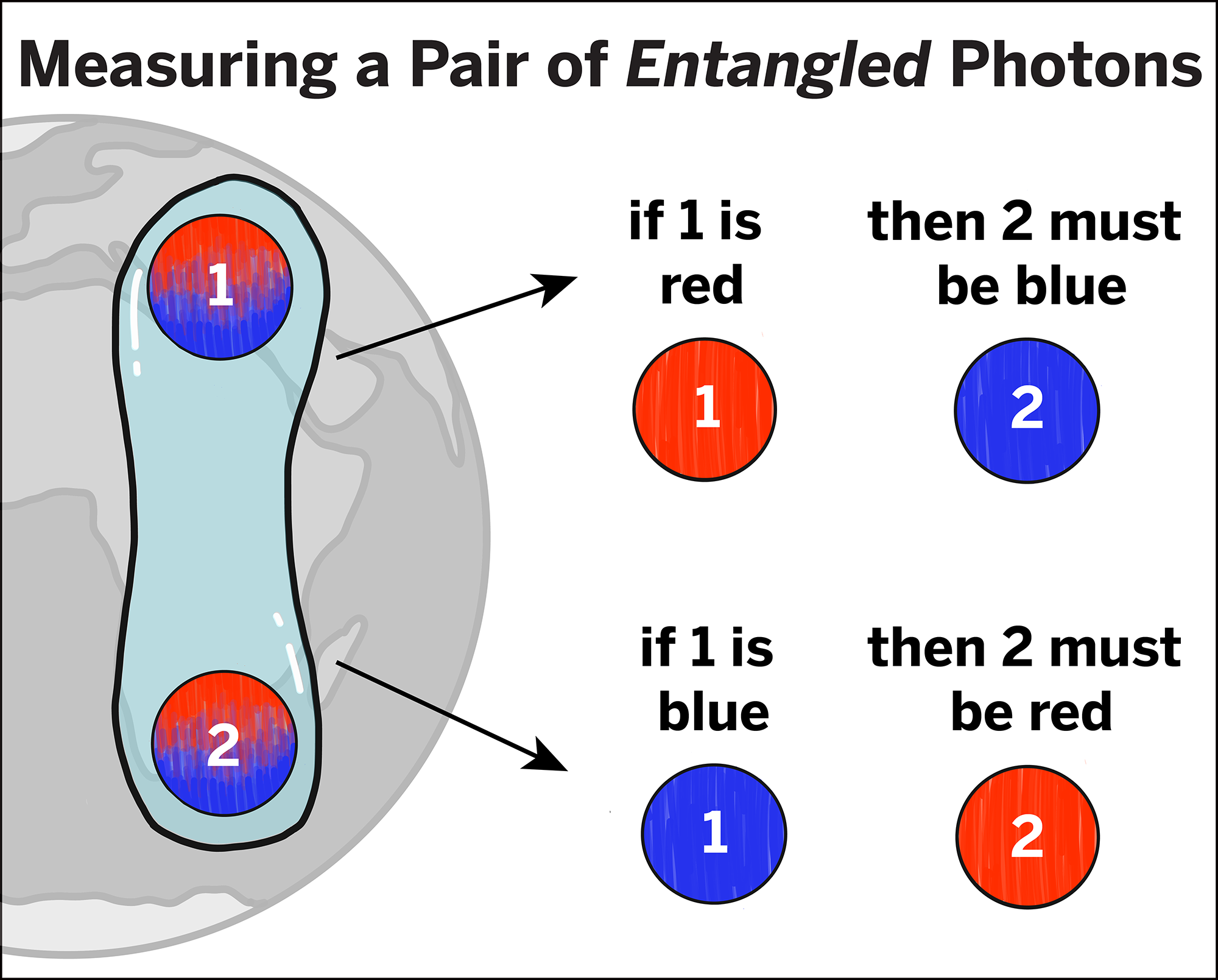

Entanglement

Another important property of atoms is entanglement. This is when atoms “connect” to each other like telepathy. They aren’t physically connected, but one’s state controls the other, instantaneous changes happen even when connected from light-years apart. No one knows how this works. In quantum computing, atoms need to be entangled for it to work. This allows for one’s state to affect another, so that an operation on one qubit does the same operation on all the other qubits. This is also useful for certain algorithms that measure things to remove certain states, such as Shor’s algorithm I talk about later. It wants the measurement of one qubit to affect the others without measuring them themselves (remember to keep a superposition you cannot measure the qubit), which can only happen with entanglement. Without entanglement, quantum computers cannot work.

Image courtesy of The Quantum Atlas

Algorithms

Shor's Algorithm

Shor’s Algorithm is an algorithm to factor a number. This can be used to break encryption, which keeps all info on the internet safe. Most encryption, or garbling of data, is encrypted in a way such that it can only be decrypted if someone has the factors of a number, or spends a ridiculous and impractical amount of time finding the factors of the number. But Shor’s Algorithm makes it incredibly simple, and could access a huge amount of hidden information. A theoretical 4099-qubit quantum computer would be 946,080,000,000,000,000,000 times faster than a regular computer with 15613564 times less units of info.

Shor’s Algorithm essentially boils down to choosing a random guess, and turning it into what’s likely a correct guess.

The Math

Start with a number to factor \( N \), and a random guess \( g \). First, try to find the greatest common divisor of \( N \) and \( g \). If there is one (not including 1), we’re done, that’s it, we found a factor of \( N \). But usually it won’t be right.

One essential property of \( N \) and \( g \) is that because they’re coprime (no common factors), some \( g^p \) has to equal some \( m \cdot N + 1 \). For example:

- \( 7, 15: 7^4 = 160 \cdot 15 + 1 \)

- \( 42, 13: 42^3 = 5699 \cdot 13 + 1 \)

\( g^p = m \cdot N + 1 \) can be turned into:

\( (g^{\frac{p}{2}} + 1) \) and \( (g^{\frac{p}{2}} - 1) \) are the two new, better guesses. So it just needs to find some value \( p \) that creates a multiple of \( N \), + 1. It then takes the two better guesses, and gets the GCD of each value and \( N \), and those final results have a 37.5% chance of being factors of \( N \).

For example, if \( N = 15 \) and \( g = 7 \), we guess \( p \)'s until we find the right one, 4. This is correct because \( 7^4 \) is a multiple of 15, + 1, \( 160 \cdot 15 + 1 \). We then find the two new guesses:

We then find the GCD's of those and the original \( N \):

So the factors of 15 are 3 and 5.

It’s only correct 37.5% of the time because of two possible cases:

- One new value may be a multiple of \( N \), so the other is a factor of \( m \), making neither useful.

- \( p \) in \( g^p = m \cdot N + 1 \) may be odd, which makes \( \frac{p}{2} \) a fraction exponent which means we can’t find the answer.

Up to this point, this can be done on normal computers, but it’s not very useful because it’s still slow.

The Quantum Computer Implementation

On quantum computers, \( p \) is found by using a superposition with numbers that destroy each other if they aren’t correct.

First it uses a superposition of possible \( p \)'s, then turns that into a superposition of all \( p \)'s and \( g^p \)'s, then turns that into a superposition of all \( p \)'s and how much bigger they are than a multiple of \( N \) (remainder)

But how do we get all incorrect answers to destroy each other?

Here’s the essential principle:

Let’s say one of the random guesses is 26, and it happens to be 5 more than a multiple of \( N \)

If we find the correct \( p \) value that makes \( m \cdot N + 1 \), that means:

And so on for any multiple of \( p \).

So now we have a superposition of all \( p \) values and how much bigger their \( g^p \) are than a multiple of \( N \) (\( r \) value). If we randomly measure one of these \( r \) values, we are left with the \( p \) values that have that measured \( r \) value becuase of the properties of entanglement. Now all of these possible \( p \) values are the correct \( p \) apart from each other, because of the principle mentioned above.

Without getting into exactly how it works, this is brought through a Quantum Fourier Transform, which outputs a random number over p, \( \frac{x}{p} \). We then run this multiple times, and it will be clear which number these are all over, \( p \).

Video example:

Grover's Algorithm

Grover’s Algorithm is used to find an element in a list in on average \( \sqrt{n} \) guesses instead of n/2. The algorithm starts in a state that is a superposition of all n elements in the list. At this point, it already knows where the value it’s searching for is, but it can’t just measure it because then it will randomly choose an item in the list. So instead it applies something called the “Grover diffusion operator”, which essentially inverts and uninverts the correct answer, which increases the probability of it being picked when measured. Repeating this over and over, it will eventually reach \( \frac{\pi \sqrt{n}}{4} \) probability of being picked. This is why it needs on average sqrt(n) guesses to correctly randomly guess the right option in a list. In a list of, for example, 1,000,000 items, this means it requires on average 1,000 guesses compared to 500,000.

Image courtesy of ResearchGate

Theoretical Applications of Quantum Computers

Encryption

Breaking It

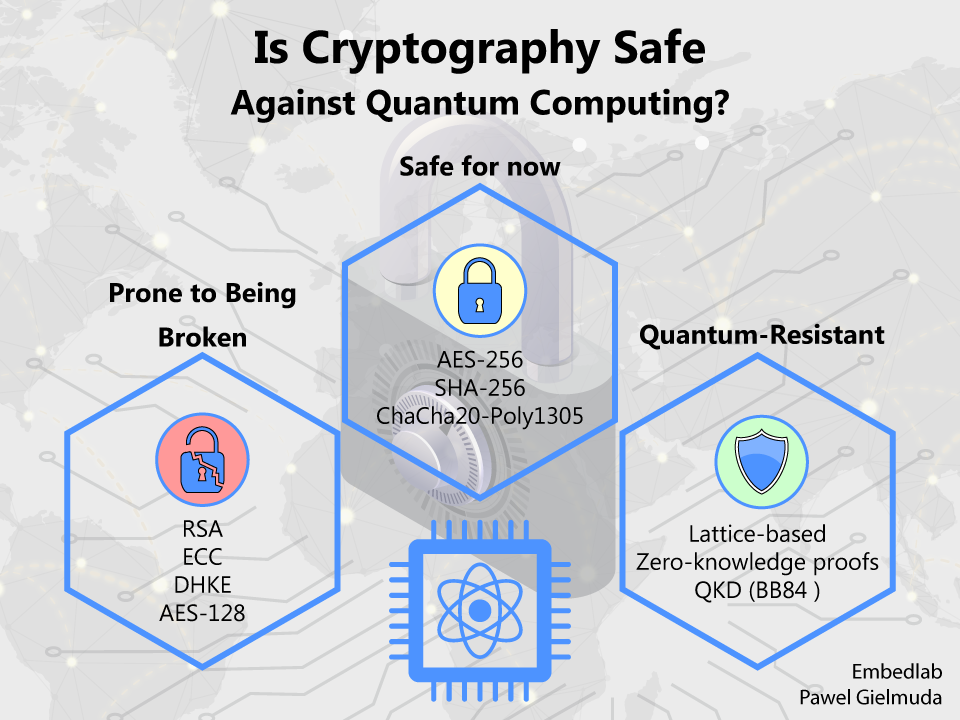

As explained above, Shor's Algorithm can factor numbers ridiculously faster than classical computers. The extremely popular RSA encryption method banks on not being able to factor large numbers quickly. But Shor's Algorithm destroys that, allowing Quantum Computers to essentially access all information on the internet. This would/will be devestating for security.

Here are some examples of cryptography and if they are safe from Quantum Computing:

Image courtesy of Medium

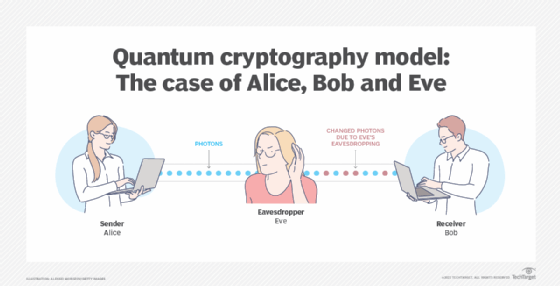

Improving It

Quantum Computers can also create new encyrption keys that are encoded and transported through qubits, making them even stronger than current encryption. These would be safer than current encyrption methods from a both classical and quantum standpoint. For more info, check out this article.

Image courtesy of TechTarget

Science

Quantum Computers can, obviously, simulate quantum processes really well. Because of this they can simluate entire biological systems, chemical compounds, and most scientific things really well, extremely accurately and quickly. This can even theoretically simulate interactions between all proteins in the human genome. This has profound implications for the field of pharmaceutics, where virtual labratories with incredibly high accuracy and no ethical concerns may become the norm.

Parallel Computing

Quantum Computers are masters at parallel computing, in which multiple calculations are preformed at the same time. All calculations in a CPU of a regular computer are preformed in order. Quantum Computers, because of superposition, can do many calculations at the same time. Basically they are just better than traditional computers in processing information. They're faster in terms of equations and lists, they're able to compute things at the same time, and they take much less data to do the same thing as a traditional computer.

Why Quantum Computers are currently impractical

- Shor's algorithm, the algorithm I talked about earlier that may be used to break encryption, has only factored 35. And that was only once. It has only factored 21 consistently. This is incredibly low, a regular computer can factor 35 in less than a milisecond.

- The longest time that the largest quantum computer has been in operation (atoms were entangled) is 0.0008 seconds. This is because of the extremely high sensitivity of qubits.

- Entanglement can only happen when almost absolute zero temperature. Quantum Computers need to be in special containment areas where they can operate at almost absolute zero temperature. And as I just explained, this still only allows it to work for literal microseconds.

- However, photosynthesis is done using entanglement, and that occurs at room temperature. So if we could understand how entanglement occurs in those conditions, we can apply it to Quantum Computers.

- They're extremely expensive - At least $10,000,000 for a good one

Additional Resources

Logic Gates Rotate Qubits, a video explaining what qubits are more specifically and how they are changed

How Quantum Entanglement Works, a sequel video to the previous explaining how it applies to multiple qubits

Quantum Supremacy by Michio Kaku, a book that was very useful for my understanding of this topic

Shor's Algorithm Explained, if you didn't understand my explanation this may be more visual

The Map of Quantum Computing, a video explaining many concepts in Quantum Computing including some I didn't cover

The Map of Topological Quantum Computing, a video explaining many concepts in Quantum Computing, but more focused on the actual physical implementation rather than the ideas behind it